SURVIVOR STORIES

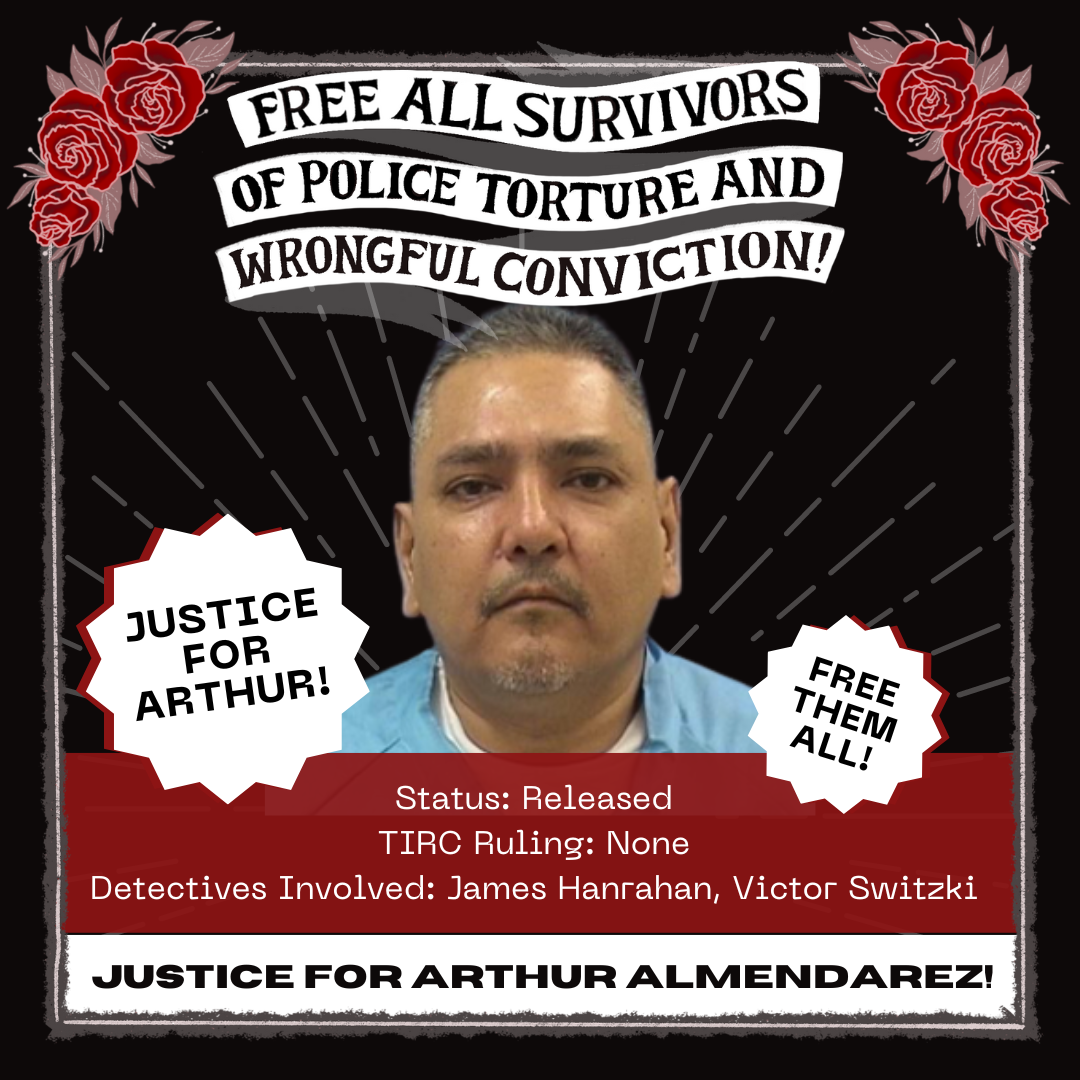

ARTHUR ALMENDAREZ

On September 21, 1986, at approximately 4 AM, a fire swept through a two flat house at 2603 West 24th Place in Chicago. The Martinez family lived in the upstairs apartment. Siblings Blanca Martinez and Jorge Martinez escaped, but their two brothers, Guadalupe and Julio, died in the attic. The police suspected arson. Their investigation eventually led to John Galvan, Arthur Almendarez, and Francisco Nanez.

THE INVESTIGATION

Initially, a woman named Lisa Velez was the prime suspect. Velez believed that the Latin Kings gang had killed her brother in a shooting one year prior to the crime. Jorge Martinez, who survived the fire, was a member of the Latin Kings. According to statements made to police by four witnesses in this case, Velez had threatened to burn the Martinez house down in retaliation for the killing of her brother.

Police began by interviewing victims and neighbors. Velez managed to avoid investigators until several months into the investigation. When brought in to be questioned, she confirmed that she and Jorge Martinez were arguing in front of the house a day or so before the crime. Velez alleged that she had seen John Galvan, Vincent Vega and Michael Almendarez walking by during the argument, and that Vincent Vega had claimed that he would avenge the death of Velez’s brother.

POLICE MISCONDUCT: THE ARRESTS AND INTERROGATION

On June 8, 1987, nine months after the fire, police officers went to Almendarez’s home and asked him to come to the police station. Almendarez was five days shy of his 21st birthday. He was married and working two jobs. He went willingly to the station, with the understanding that he was being asked to provide information about another case that the police were investigating. He assumed that he would soon return home. He later testified that he was taken to a small room at the police station where an officer grabbed him by the throat, and told him that if he cooperated, “this will all go smoothly.” Four officers, including Detective Switski and Detective Hanrahan, punched, kicked, and grabbed him, telling him he would tell them “what [they] wanted to hear” no matter how long it took. Detectives Switski and Hanrahan repeatedly tried to coerce Almendarez into signing a statement that implicated John Galvan with a motive for setting the fire: According to police, Galvan had allegedly been targeted in a shooting two weeks earlier by “some people” who lived on 24th Place, and he wanted retribution. Almendarez denied knowing anything about the fire and called the police account a lie. He told police that the conversation between Galvan, Nanez and Almendarez about setting the fire had never occurred. Police then switched the story and said that it was Almandarez who asked Galvan and Nanez for their help in burning down the house. Again Almandarez declared this a lie and asked to make a phone call. He was chained to a wall. Detective Hanrahan slapped Almendarez and kicked him in the groin. Detective Switski threatened that it in the end it was going to either be Almendarez or Galvan. Almendarez was told to face the back of the elevator, and a hard object that felt like a gun barrel Arthur Almendarez was put to the back of his head. Detective Switski told Almendarez that he could take him to the basement and shoot him in the head and no one would care--he could just say that Almendarez was trying to escape.

At that point Almendarez, no doubt terrified, agreed to cooperate. He made a hand written statement reflecting the police’s account of the events-- that he had been with Nanez and Galvan on the night of the fire and that Galvan had asked him and Nanez to buy gasoline, because he wanted to burn the house on 24th Place. They got the gasoline and drove to 24th Place, where they walked to the alley. Nanez and Galvan went into the alley and started the fire by throwing a bottle of gasoline at the house, lighting it with a cigarette. Almendarez signed the statement, believing that the police would honor their promise to let him go and that he would later be able to explain the circumstances that led him to sign. Instead Almendarez was taken to Cook County Jail. He told medical staff he was injured, but nothing was done about it.

Michael Almendarez, Arthur’s brother was also arrested and brought in for questioning. Michael later testified that he was not with his brother Arthur, Galvan or Nanez on the night of the fire. He testified that officers pressured him to confess, hitting him in the stomach and threatening his life. They handcuffed him, took him to a rival gang’s neighborhood and said they would leave him there. So, Michael gave in. He was taken back to the station, where a group of officers wrote a confession stating that Galvan and Nanez admitted that they were responsible for the fire. Michael signed, but the next day he went to the grand jury and repudiated his statement.

RELEVANT INDIVIDUALS

Jorge Martinez: Survivor of the fire, member of the Latin Kings

Blanca Martinez: Survivor of the fire

Lisa Velez: Made threats of arson to the Martinez family

John Galvan: Co-defendant charged with starting the fire in the Martinez house. Prosecutors said it was because members of the Martinez family were allegedly in a rival gang

Isaac Galvan: Brother of John Galvan

Arthur Almendarez: Co-defendant of John Galvan

Michael Almendarez: Brother of Arthur Almendarez

Francisco Nanez: Co-defendant with John Galvan & Arthur Almendarez

Socorro Flores: Eyewitness of the burning of the Martinez home and witness for the defense

Frank Partida: Witness for the defense

Jose Ramirez: Witness for the prosecution

Jorge Rodriguez Witness for the prosecution

THE TRIAL

Socorro Flores lived across the alley from the Martinez home. She testified that she woke up around 4 AM to make her husband’s lunch for work. From her second floor kitchen which looked out onto the alley she heard and saw boys (teens) talking and walking. One threw something that landed on the porch of the Martinez house and started burning. She ran out of her house to alert people to the fire. She could not see the face of the person who threw the bottle with gasoline and was unable to identify anyone in a lineup at the police station.

Partida submitted witness statements stating that he would have recognized Almendarez if he had been in the alley the night of the fire. He had known Almendarez since he was a boy and later coached him and Galvan in a sports league. But, Partida was never called to testify and did not learn of the trial until it was over.

At trial Ramirez implicated Galvan saying that he had seen him, someone named Michael and two others at the crime scene before the fire had started. After the fire department arrived, Ramirez stated that he saw Galvan’s brother, Isaac standing near the burning house.

Rodriguez denied seeing anyone in the alley before the fire but claimed to police that he later saw Galvan and Galvan’s brother Isaac standing on the street watching the fire. Rodriguez did not testify at the trial. Police Detective Hanrahan later testified at Galvan’s suppression hearing that Rodriguez (who is since deceased) did not see Galvan.

No witnesses placed Arthur Almendarez at the scene of the crime.

Galvan was tried by a jury in 1989. Almendarez and Nanez were tried simultaneously by separate juries in 1990. All three were found guilty of aggravated arson and two counts of first degree murder and sentenced to life in prison.

THE APPEALS

In 1988, long before Almendarez was tried, he filed a motion to suppress his statement to the police, which described the physical abuse he endured and the psychological coercion which resulted in his hand written statement. At a hearing on this motion, Detectives Swistki and Hanrahan testified that no physical abuse occurred and no promises were made to persuade him to write a statement.

In March, 2001 Almendarez filed post-conviction petitions that a life sentence was unconstitutional. HIs case was assigned to Judge Epstein who appointed the same public defender for him and for Galvan.

Over the next several years Galvan and Almendarez continued to file post-conviction petitions concerning the State’s disregard of evidence concerning police abuse, failure to call witnesses, jury selection bias, and other issues. In 2004 Judge Epstein denied the state’s request to dismiss their petitions in both cases and set an evidentiary hearing.

Meanwhile the post-conviction defense counselors sought evidence to demonstrate patterns of police misconduct taking place in the headquarters of the Chicago Police Department Area 4. In 2005 defense counsel requested to subpoena records in several other cases of complaints against Detectives Switski and Hanrahan from the Police Department’s Office of Professional Standards. Judge Epstein allowed the motion. But the State continued to file multiple motions to stop the progress of the case. Judge Epstein expressed his “frustration at the length of time it was taking to set a final date for the evidentiary hearing.” A final date was set for July 31, 2006.

However, before the hearing could take place, Judge Epstein was transferred to the Civil Division. The case was then assigned to several different judges over a period of 14 months. Before a hearing occurred, each new judge would grant the State’s motion to reconsider, dismissing Alemendarez’s petition. Eventually the case was assigned to Judge Brosnahan, who initially agreed with Epstein’s rulings. But on September 23, 2008, Judge Brosnahan reversed her ruling, stating that “after reviewing the record a second time, she did not believe Judge Epstein had given the State ‘a fair shake’ at the earlier motion to dismiss.”

Almendarez continued to appeal. The State continued to keep the appeals from moving forward. In 2013 a three judge appellate panel finally ruled that the Almendarez case be remanded to the circuit court for a third stage evidentiary hearing. In their ruling the judges stated: ”…there were no eyewitnesses who placed defendant at the scene. There was no physical evidence connecting defendant to the crime and he was convicted based solely on his handwritten confession.”

An evidentiary hearing was finally held. It lasted 14 days. Twenty three witnesses were called for the defense. Seven of them had been defendants in other cases involving Detective Switski. Each of the seven testified that they had been physically abused by Switski. At least one had sent a letter to the Office of Professional Standards about Switski’s conduct. Five testified that they had confessed to false statements prepared by police officers. At the hearing Switski denied having any memory of investigating Almendarez or of taking confessions from him, the testifying witnesses or other witnesses.

IS THE END IN SIGHT?

The trial court ruled against Almendarez. He continued to appeal. Years passed. On January 24, 2020-- 29 years after the initial trial and 32 years after Almendarez’s arrest-- a three judge panel of the appellate court reversed the trial court’s ruling and ordered a “new suppression hearing, and if necessary, a new trial”. In their ruling the judges found that previous decisions had essentially declined to consider evidence of abuse by police. The appellate court made a similar judgment in the Galvan case a few months earlier.